On Ethical Systems and Superheroes

Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links, meaning I get a commission if you decide to make a purchase through my links, at no cost to you.

I find myself thinking deep thoughts about superheroes often. It’s weird. I’m weird. We’re all weird. But I wanted to share some of these thoughts with you on ethical systems and superheroes.

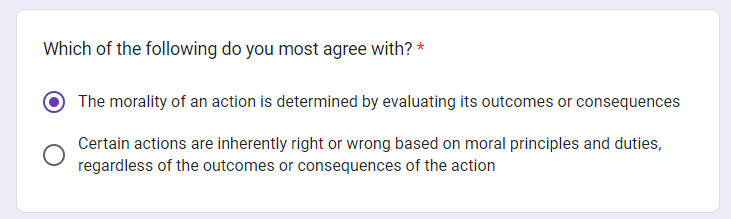

I was doing a questionnaire on my morality and ethics earlier today. Someone asked me to do it for their class, I’m not sitting around looking for this stuff (believe it or not). And I got this question.

A question about ethical systems. I add in superheroes later.

I think it’s an interesting one. I’ve never been one to ponder my ethical systems from a strictly philosophical point of view. I have policies I support, I have reasons I want to enact those policies, and I have broad goals that I would like to see achieved through policy. But I don’t have this deep understanding of philosophical concepts. My interest is more in the pragmatic, in the political, despite the fact that I know one is derived from the other.

But I have been thinking recently about the philosophical systems that underlie my beliefs, and have been occasionally trying to peg myself down to one. I don’t think there is one. I don’t think there is a correct answer.

But here we are, in what seems to me to be a decision to choose either utilitarianism (the first choice) or deontology (the second one).

It’s funny, because when I consider my own ethical beliefs, I think the closest thing that describes me is “rule utilitarianism”, which is the belief that we must follow rules and systems that, on their whole, lead to the greatest outcomes. So that first choice, while not rule utilitarianism, would be the correct choice for me.

But whenever I find myself thinking about superheroes, my ethics suddenly change. I believe that superheroes have a duty to intervene. I believe that power is a gift that should be used for the greater good. Even outside of superpowers, I believe that the wealthy have a duty to pay their taxes, to contribute more than the average person to the betterment of society, to “pay it forward”.

One might even say that I believe that, with great power, comes great responsibility.

So, the second choice then?

Hmm, seems like I have a set of conflicting values then. Rules for thee but not for me, right? The powerful have moral duties and I just get to do whatever is the best (for me, perhaps?). That doesn’t sound right, though. That doesn’t sound like my ethics at all.

So let’s take a few minutes to ponder what the closest possible answer to that question is. I think it’s something in the middle, but let’s try to find what that middle ground is. Let’s see if I can rectify these conflicting beliefs and come to something coherent.

Let us ruminate on ethical systems and superheroes.

We’re exciting people here, aren’t we?

Actual photo of my dying moments.

Definitions

There’s no way we are doing this without some definitions.

Utilitarianism is the belief that an action is “right if it tends to promote happiness or pleasure and wrong if it tends to produce unhappiness or pain—not just for the performer of the action but also for everyone else affected by it”. It’s derived from consequentialism, but we’ll (probably incorrectly) use those terms interchangeably, and sum up the definition as saying that an action is good if it produces good outcomes or consequences. English philosopher Jeremy Bentham is considered the founder of this ethical system, and John Stuart Mill is likely the most famous name attached to it.

That’s clearly Choice A on the image above.

Then there’s deontology, which is the belief that says “actions are good or bad according to a clear set of rules”, and that “From an ethical perspective, personhood creates a range of rights and obligations because every person has inherent dignity – something that is fundamental to and is held in equal measure by each and every person”. It is often associated with inherent duties and fundamental responsibilities. The Hippocratic Oath that all medical professionals take could be seen as an example of that, as doctors are widely considered to have a duty to help someone who is sick or injured, no matter the situation. German philosopher Immanuel Kant is probably the top name associated with this.

That’s clear Choice B.

It should also be noted that Divine Command Theory–the idea that moral law is absolute because it comes from God–is derived from deontology, though not all deontology is Divine Command Theory. Any appeal to a universal moral truth, however, is derivative of deontology.

Conversely, it appears to me that appeals to moral relativism would be an appeal to consequentialism, the umbrella under which utilitarianism is. I emphasize “to me” because my research doesn’t seem to link the two together so neatly, but it intuitively seems to be right. If an action is right or wrong depending on the consequences, then wouldn’t the morality of an action be relative? Wouldn’t killing someone be moral or immoral depending on what the consequences of killing that person is?

I dunno.

Now, there is a lot to write about these ethical systems (and others, such as virtue ethics). Entire essays–entire books–have been written on them. They have been the subject of much debate and exploration over the course of literal centuries, and there’s nothing I can write here that can do any of it justice. Even asking that question on the questionnaire as multiple choice is a simplification to the point of absurdity.

But we are going to plow through this with all the grace of a bull in a china shop, and we are going to explore these ethical systems in the context of men who put on flashy tights and beat each other up with superstrength.

So up, up, and away to a discussion on ethical systems and superheroes!

Utilitarianism or Deontology? A or B?

So there’s a lot to consider here. Is the morality of an action determined by evaluating its consequences and actions, or are certain actions inherently right or wrong based on moral principles and duties, regardless of their consequences or outcomes?

My immediate judgment, if I had to pick, would be the first choice. After all, we can talk about some innate, inherent duties granted to us by nature/God/evolution/whatever here, but at the end of the day, something is either good or bad. Something either gets good outcomes or bad outcomes.

But it seems like the entire superhero-reading/viewing public has already determined otherwise, right? From the very beginning, superheroes have been acting out of a sense of moral duty. I’m reading through all the Nedor comic book lines from the early 1940s. Characters that are now in the public domain, such as Black Terror, Doc Strange, the Liberator, the American Crusader. All of them start the same way. They get their powers somehow, and immediately decide that they have to use their powers to fight for America against the Nazi threat because it’s the right thing to do.

This pattern continued, with Spider-Man learning the hard way that with great power comes great responsibility. We see in The Boys a world where superheroes act to maximize their own pleasure rather than with a moral sense of responsibility. They’re mainly a collection of sociopathic monsters, all with the exception of a few.

And Avengers: Infinity War and Endgame brings this to a head spectacularly. Thanos seeks the Infinity Stones not to impress Lady Death, like in the comic, but for the greater good. The films don’t question the fact that his actions would have saved the universe from overpopulation and complete consumption of all resources if it weren’t for the heroes’ intervention, yet it never even takes a moment to question whether or not he even has a point. The film says straight out that his actions will lead to the best possible results for everyone in the universe, and then says straight out that his actions are evil and must be stopped.

Thanos acts with outcomes in mind. A utilitarian. A morally relative scenario where the consequences of killing on a mass scale are actually good.

The superheroes–from Iron Man to Captain America and everyone in between–act out of a sense of duty to protect life. Deontologists. A universal moral truth that life should be protected no matter what the consequences may be.

So, I guess that settles it, right? Superheroes are collectively deontologist, the second choice is the correct one, and I as a utilitarian am supervillain scum that has no business enjoying this genre. I guess that’s why I’m one of those people that thinks that someone should just kill the Joker already.

But that doesn’t seem to be quite satisfying. I feel like there’s some middle ground here. Something that allows me keep my utilitarian beliefs while also keeping to the principles that are so ingrained into the fabric of the superhero genre.

It could just be that I haven’t really done as much reading on this as I should (I mean, again, I don’t really think in terms of ethical systems, and I won’t even pretend to have grasped the last philosophy book I read nearly twenty years ago). But that seems like a cop-out, too. No, I think that there’s a connection point here that connects both ethical systems and superheroes’ fundamental ideologies.

So, I said before that, despite not really looking into this stuff, I’ve kind of settled into a specific ethical system for myself. I did so while listening to political streamers talk and debate each other on the topic. And while I did very little reading, I have heard different arguments for different things and one just sort of popped out at me as making the most sense.

And that is, as I mentioned earlier, “rule utilitarianism”.

Rule utilitarianism seeks to sort of fix the issues with utilitarianism where any horrible act could be justified because “the ends justify the means”. Whereas regular or “act” utilitarianism judges an action based on whether it produces a good outcome, rule utilitarianism places the onus of good outcomes on a set of rules and then judges the act based on adherence to those rules. In other words, an action with bad outcomes can be judged as good if it follows rules that generally produce good outcomes, and vice versa.

A YouTube streamer I follow gave a pretty fun hypothetical to illustrate the point. I’m going to try to relay that by memory:

Say you have a person standing on an overpass throwing bricks at the cars below. One of them breaks through a windshield, and the driver loses control of the car and crashes. The driver survives and is mostly fine; he'll need to go to the hospital for a few days due to some broken ribs and the like, but is fine and should be out within the week. But during all the testing and the X-rays and everything, a growth is found that, if untreated, will grow into a malignant tumor. Cancer. Fortunately, the growth is immediately removed and the driver is cancer free, all because he got X-rayed early on, which in turn was all because he got a brick thrown at him while he was driving. Would we judge the actions of the brick thrower as good because they led to such good outcomes? Under rule utilitarianism, no. Because it is a massive net social harm to allow overpass-brick-throwing to become normalized. The next brick isn’t going to find another malignant tumor. As a rule, this behavior must be punished even if it led to good outcomes in this one very specific instance.

So what we’re looking at now is a sort of compromise position between purely act utilitarianism and universal moral truth deontology. We’re looking now at systems that judge actions based on rules. Rules which measure outcomes, and rules which abide by universal moral truths. And it’s here that we can start to evaluate the deontology, the inherent moral duties, that drive superheroes under an outcome-driven utilitarian framework.

Because we can now explore where those deontological moral obligations and duties come from.

Let’s look again at the Avengers films. Was Thanos acting under utilitarianism? Or was it the superheroes? At first glance, it was Thanos. But let’s apply some rule utilitarianism. Sure, let’s accept that wiping out half the universe had better outcomes on paper, but there are intangibles to consider as well. The mental and emotional pain and suffering inflicted on the surviving half. The loss of scientific, mathematical, and other analytical expertise when those individuals disappeared during the Snap. The drain on the resources of individuals having to assume the care of children, elderly, sick, and disabled people when their caretakers disappeared. And, most importantly, that mass genocide produces such terrible results–even in a situation like this where it could potentially be justified–that it must always be judged negatively as a rule.

In other words, normalizing or even just once allowing the elimination of half the universe is, as a rule, bad. Allowing the action to either happen or go unpunished produces negative outcomes, so therefore it must be opposed.

Or let’s go back to Spider-Man. Peter Parker was originally selfish and greedy, until his unwillingness to do what’s right led to the death of Uncle Ben. But later on, it was because of his actions and his crimefighting in general that Gwen Stacy died. In other words, because Spider-Man decided to use his powers for good and be a crimefighter, Gwen died.

So Ben’s death made him go from acting selfishly to selflessly, but Gwen’s death did not send him back to acting selfishly. He continued to be a superhero, following the lessons of his uncle’s death but seemingly not the lessons of his girlfriend’s. Why?

Moral obligation could be part of it, but we see that he only learned about moral obligation and duty through consequences. He saw the consequences of not acting for the greater good. And even though he saw that acting for the greater good killed Gwen, he continued to act in that way. Because the evaluation of his actions (acting selfishly and using his powers for greedy ends, or acting selflessly and using his powers for good) are not based on the consequences of any individual action, but a rule. It is generally better to use your powers responsibly and to help others, and so he does regardless of whether or not any individual battle saves a life or dooms it. After all, not only did his inaction get his uncle killed, but he had rescued ordinary people from harm time and time and time again.

To put it as succinctly as I can, Spider-Man not acting as a superhero would have far more negative consequences than Spider-Man acting as a superhero, even though Spider-Man acting as a superhero is specifically what led to the death of Gwen Stacy.

Or to condense it even further: It produces better outcomes for society if, as a rule, those with power (be it wealth, influence, or superpowers) use them to help the less fortunate. Even if there’s a specific situation where using that power allows for harm to come.

And therefore, “With great power comes great responsibility” is justified not on an inherent moral truth, but on an evaluation of outcomes and consequences.

My Final philosphical thoughts

To be clear, there’s no correct answer to any of this. Nor do I think any popular superhero comic or film writer ever sat down and labeled their character’s exact ethical system.

All we did was create a way for the two answers to that philosophical question to apply to superheroes with minimal contradiction.

We created a way for someone who believes in judging an act by its outcomes and consequences to believe in the moral duties and obligations of superheroes and, by extension, those in power.

If we were to agree that maximizing human well being and minimizing human suffering produces the best outcomes (as we generally do simply by looking at our own individual experiences), then the follow-through is that our various government, media, financial, and cultural institutions–which have the most societal power–should act in ways that maximize that well being. Then we would want for the government to, say, end homelessness by giving homes to the homeless or combatting child food insecurity through school lunch programs, and we would want other powerful institutions and individuals to step in and contribute to solving the problem as well.

Even without invoking the universal moral truths of deontology, we could say that the benefits of having our society work toward the benefits of everyone in this way produces such massive positive outcomes as a general rule that there is almost a responsibility (or duty or obligation) of anyone with outsized levels of power to step in and help in some way. Even if it’s just through the wealthy paying all the taxes they owe and not hiding their money in offshore shell companies, or content creators with large platforms directing their audiences towards positive causes.

The benefits of those with power helping those without is such a good thing in terms of outcomes that it creates a duty to do so, even if there’s some edge case scenario where something might go wrong (a specific program doesn’t produce the expected results because of poor implementation, or a child chokes on their free school lunch, or Peter Parker being Spider-Man leads the Green Goblin to specifically find and kill Gwen Stacy).

To apply it to superheroes, the benefits of beings with immense power using their gifts to benefit humanity is so positive in their outcomes that it creates what could be referred to as a “moral duty” to expect them to do so. Because there is great social harm if we allow Lex Luthor to go unpunished in stealing forty cakes.

Someone really liked the “Lex Luthor stole 40 cakes” meme.

Also, I feel like I’ve got a better grasp of moral systems than both Lex Luthor and Pa Kent. Perhaps they should take a look at Travis Smith’s Superhero Ethics, which dives deeper into ethical systems and superheroes than I possibly could.

For exciting superhero fiction written by me, be sure to check out the BLUE EAGLE Universe!